Seven connections to help us create change

22 July 2021

Learn about Action Tutoring’s conversations with local MPs this summer.

We know that what happens on programmes is important. But in an average session, do the pupils and their tutors feel how significant their actions truly are?

Extra marks are gained, concepts are grasped for the first time, new future chances open up slightly more each time a pupil turns up and tries. But beyond individual growth, what happens matters on a greater scale. Everyone involved in our programmes is part of a nationwide movement, where people show up in the belief that a great education can make a more equal society.

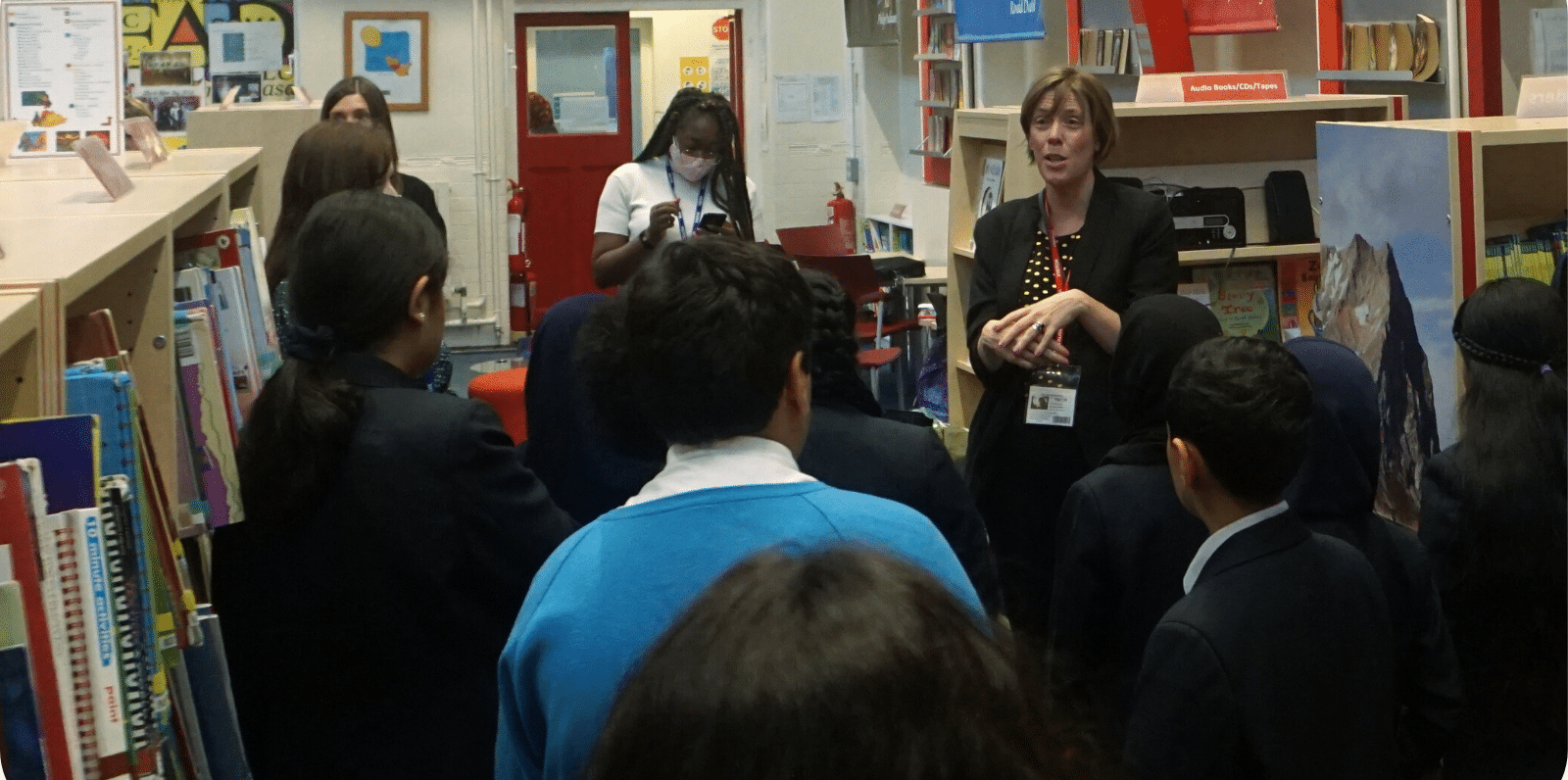

Sometimes an opportunity arrives to show pupils and tutors that their efforts are being noticed. At 12pm on Friday 2nd July our Programme Coordinator, Sam, was about to set up for the usual afternoon session at Heathfield Primary School in Nottingham. Things felt a little different, though; two journalists and a camera person were expected at the school reception. The Member of Parliament for Nottingham North, Alex Norris, and our Interim CEO, Jen, would soon be arriving.

Not long after our first programme launched in Nottingham in 2019, Alex agreed to visit an Action Tutoring partner school to see the work being done. When the pandemic closed school doors, the visit couldn’t go ahead. Alex still helped us to get the word out to others at a crucial time via his newsletter.

It was an exciting moment, then, to finally welcome Alex to a session at Heathfield Primary School in July this year. Sam told us about the atmosphere on the day. “The pupils buzzed with a mixture of excitement and nervousness at the opportunity. Their heads were down and focused despite copious distractions. Some were even more studious than usual in a bid to impress their local representative!”

This was a chance for everyone to celebrate the admirable effort pupils had made since November. Sam could see how motivated they were to show off their work and quiz the MP. “The challenging questions they posed to Alex were certainly testament of this, as well as their working-strewn whiteboards which they returned to me at the end of the session.”

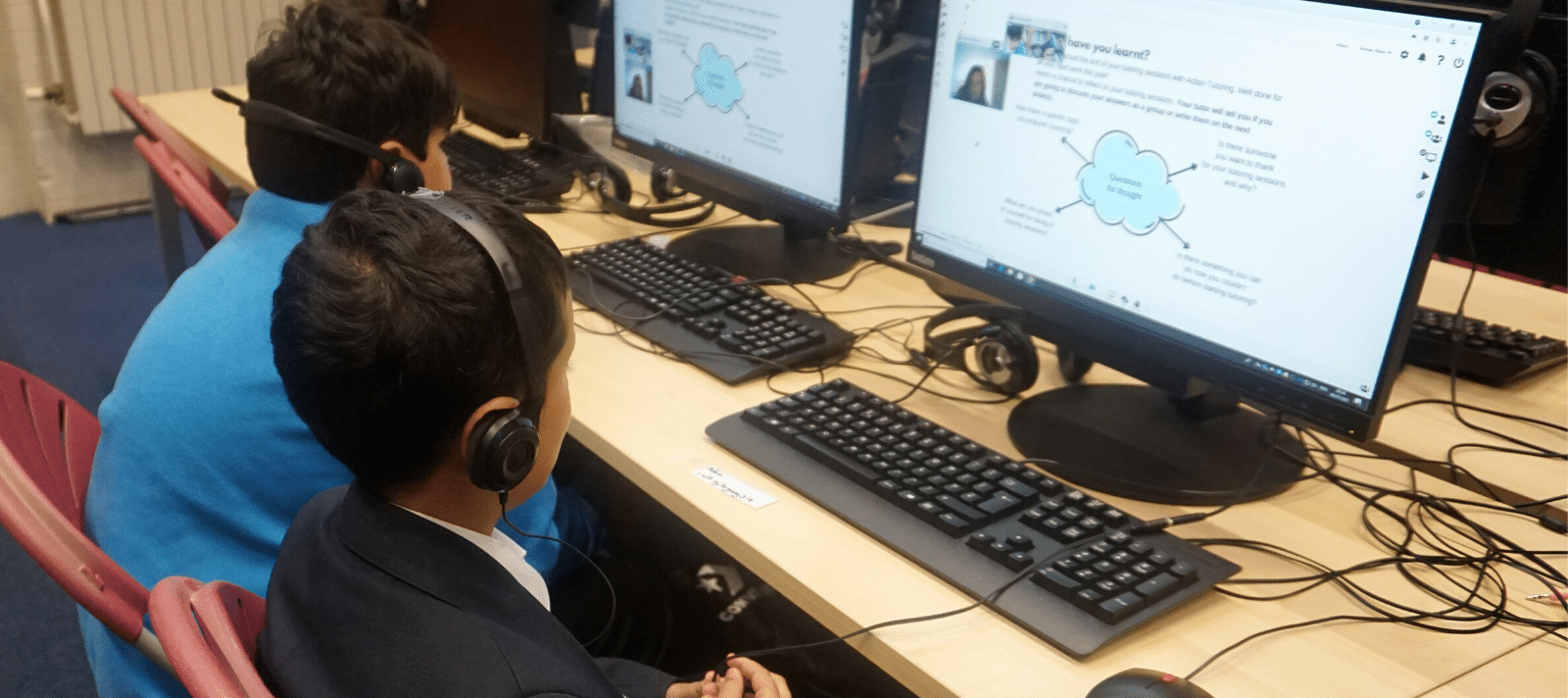

Less than a week later, a similar moment was about to happen at Ark Victoria Primary Academy in Birmingham. The committed MP for Yardley, Jess Phillips, had already witnessed local tutors working with pupils at another partner school back in 2017. But this time, circumstances were quite different. At 8am on Thursday 8th July, just before Jess arrived, tutors were logging in from Birmingham, Cambridgeshire, Exeter and beyond, ready to lead a productive and joyful final session with the Year 6s at Ark Victoria.

Justina has been tutoring at the school since last November and helped her pupils formulate questions to ask Jess Phillips during the visit. “It has been an incredibly rewarding experience to volunteer and support the learning of year six pupils remotely, at a primary school local to me in Birmingham.

“Despite the disruption caused by the pandemic over the last year, my pupils have shown enthusiasm, been willing to learn and have continued to make progress. I’m really looking forward to next year.”

This was the last session for Year 6 at Ark Vitoria after a big year. Another exceptional tutor, Elaine, has been on this journey with the pupils whilst living elsewhere in the country. “As the school year draws to a close, I am really reflecting on how lucky I have been to be able to work with the pupils at Ark Victoria Primary. They have been so cheerful and worked so hard – a great reminder to try our best when sometimes things seem too difficult. I work with Action Tutoring because I want to help young people achieve their best and am always amazed by how receptive the pupils are to the tuition – they always make me want to do more.”

Action Tutoring is hugely grateful to Alex Norris and Jess Phillips for their time and support for these pupils. Their active interest in our work locally has provided a special end to a year of hard work by all involved in our programmes. It has also already helped Action Tutoring forge new connections in the wider community.

Action Tutoring reaches out to local leaders each year, to highlight the benefits of our work and seek support in raising awareness of what we do. This summer, Action Tutoring has met with seven MPs nation-wide to share the progress its pupils are making in their constituency, despite the additional barriers these pupils face. This seven includes two members of the House of Commons Education Select Committee. Programmes succeed because of the hard work of people in the community – whether that’s the young people themselves, volunteer tutors or the essential school team. These conversations have helped us celebrate and showcase these efforts. Going forward, we hope that deepening these connections will help us to sustain and grow the impact of our work for the unique and vibrant children and young people on our programmes.

Jumping word hurdles with pupils

1 November 2019

As the Communications and Policy Manager for Action Tutoring, I know how frustrating it can be when you can’t fix on the word or phrase that you need to get your job done.

When I first started volunteering as an English tutor, this was what I was so excited about: helping my pupils become more confident expressing themselves in writing. The more you can refine your own writing and apply the words you learn accurately, the more meaning you can unlock in complex texts and find greater satisfaction in expressing your ideas to others.

As a tutor I discovered pretty quickly that the first challenge in sessions was often ensuring that pupils understood the material, which involved slowing right down and dismantling words that had become barriers to accessing the meaning of the text.

After that, you had to start the tricky business of generating ideas about what you’d read and picking choice quotations. The final hurdle was expressing these ideas clearly by finding the right words of your own.

It sometimes stopped me in my tracks when my pupils did not know a word that I was expecting them to know, making me wonder how many other words they had passed over without asking for an explanation. I realised how important it was to check their understanding of a passage and dwell on significant words, and I made it my mission to help them acquire some of these words for the future.

I studied medieval languages at university and whenever I was trying to commit a new word to memory during my studies, I would look for a path connecting it to another word, idea, or image. I thought of it like putting up pegs in my mind to hang the new words on. The Old Norse word hegri sounds a bit like ‘egg-grey’, which could help you picture grey bird that lays eggs and remember that hegri means heron. Some words happen to have memorable stories that help you store the meaning away.

One of my favourite examples is the Old English word sōna, from which we get our adverb ‘soon’. But to Anglo-Saxons, sōna actually didn’t mean ‘soon’, but ‘immediately’: over time, our way of saying ‘right now’ ended up meaning ‘in a bit’ – a shift in meaning that we can all relate to!

I tried to put this method into practice with my pupils when I wanted them to retain more ambitious vocabulary. One pupil did not know the word ‘crimson’. I told him to think of a criminal with bright red blood on their hands, so that the sound of the word and the colour it represented would be connected by an image. Finding these pathways and pictures was a fun and rewarding way of dealing with obstacles in sessions, and I would try to revisit these words in future to ensure they were remembered.

Of course, as great as it is to teach our pupils new vocabulary and help them remember it, we also need to help them cope when they face a word that they don’t know in an exam, without getting hung up on it. Fortunately, it should always be possible to draw a valid interpretation without knowing even a lynchpin word, provided you can back it up with evidence from the surrounding text.

A good example of this is in the Old English poem The Battle of Maldon, where a word with unclear meaning appears during a turning point in the narrative. The hero is said to act with ofermōd – which has been variously interpreted in this context as meaning ‘too much heart/courage’ or as ‘excess pride/arrogance’. The events that unfold, and the representation of the hero overall, can be interpreted entirely differently depending on that one word. Although the exact meaning intended by the author can’t be known, we can accept either interpretation because both can be convincingly justified using the rest of the poem.

Our English workbooks for primary school pupils have a ‘Word Journal’ in the back pages which tutors will be familiar with: pupils are encouraged to write a new word and draw pictures around it, to help them remember it better. Although our GCSE pupils might not appreciate being asked to illustrate new words they’re learning, it is certainly worth taking time to discuss new words, write them down, and revisit them in future sessions.

Words are not only fascinating but empowering, helping you to access meaning and express yourself, and I think that is a worthy goal to have for our pupils beyond their exams: to better understand and interpret what they see, and to make their feelings and ideas more clearly understood.

Join our mission and help us provide the academic support disadvantaged young people need.

Review of ‘Social Mobility and its Enemies’ by Lee Elliot Major and Stephen Machin

30 November 2018

Reading ‘Social Mobility and its Enemies’, a new book by Lee Elliot Major and Stephen Machin.

This book is a valuable read if you want to understand the sorry state of social mobility in Britain, and why our education system alone is not levelling the playing field for young people – but we shouldn’t be demoralised.

On the topic of social mobility, Lee Elliot Major and Stephen Machin make a powerful duo: The former is Chief Executive of the Sutton Trust, a foundation dedicated to improving social mobility in the UK through evidence-based programmes, research and advocacy. The latter is Professor of Economics at the LSE with a long list of publications on the economics of education and inequality in the labour market. The two have teamed up to produce a new book on social mobility in Britain and the main forces that work against it. Given the vision of Action Tutoring – a world where no child’s life chances are determined by their socio-economic background – I was very keen to get my hands on a copy!

‘Social Mobility and its Enemies’ is a neatly presented book of unintimidating size. In the first few chapters, I learnt some new and impressive-sounding terms – including ‘intergenerational elasticity’. Although I occasionally had to ask for help to understand the graphs, overall the book is quite accessible; the authors get their messages across using metaphors, analogies and real-world examples.

Tracking trends in the economy and in education over several decades, the book shows the relationship between low social mobility and inequality of wealth and income. To use a metaphor from the book: as inequality grows and the rungs in the ladder become wider, it becomes increasingly difficult for people to climb up. The book touches on the strong incentives to help talent rise to the top, wherever it may come from – the potential for improved economic growth, leaders with an enhanced understanding of the problems and experiences of others, and the strength and innovation that diversity can bring. It also shows how the choices of individuals can harm social mobility just as much as a broken system, as often well-meaning parents hoard opportunities for their children – whether paying for exclusive tuition or renting properties to gain entry into sought-after schools – even if this exacerbates inequalities down the line or holds back a less privileged child.

The book is not a joyful read. It is full of sobering statistics and draws bleak conclusions. Some of the findings are familiar – how the top spots in many professions are still dominated by individuals educated in a small circle of elite schools. At other times, the analysis presented is more alarming: one graph, with criss-crossing lines, starkly demonstrates how children’s development up to the age of ten depends strongly on their socio-economic status: children who perform highly in cognitive tests early but come from disadvantaged backgrounds show a steady decline in performance by age ten, overtaken by less able but more privileged peers, who overcome their difficulties over time. The link between family income and test scores is particularly strong in the UK. In another dismal passage, the authors consider growing illiteracy and innumeracy in England. There are clear links between these skills, employment prospects and health, but successive attempts to reform the system have failed to improve the situation. Many continue to leave school without the most basic English and maths skills they need to get on in life.

In the final chapters, the authors explore some ways that we might sweep away unfair advantages and unlock greater social mobility: for example, the possible benefits of using lotteries to determine school and university admissions. They stress the importance of a system which nurtures talents of all kinds, not just academic ones, and pursuing policies to improve equality of opportunity at a local level. One of the strongest messages is that when it comes to education, you can’t skimp on quality or on cost. “Lives cannot be turned around on the cheap.” The authors affirm that “if we have high ambitions for education to help improve social mobility amid growing inequality, then we must be prepared to pay for it.” Schools are facing the biggest funding cuts in a generation and “teachers are among the key public sector workers who warrant higher salaries.”

However, whilst our education system can and does transform the lives of individuals, teachers on their own can’t cancel out the “extreme inequalities” outside the classroom that play such an important part in determining children’s outcomes. Implementing new approaches to teaching based on cutting-edge research can only do so much. If we want to make real gains in social mobility, we need to make education fairer and reduce the extreme inequality in our society.

Elliot Major and Machin don’t shy away from the enormity of the challenge. There is no simple or easy fix. However, other countries as well as small pockets within the UK “offer rays of light” that the situation can change. Although we may not be able to replicate the exact environment and outcomes found in countries like Finland or Canada, it is encouraging, when faced with such a formidable task, to see it that others have been able to find a better balance.

At Action Tutoring, we can be proud to be part of an evidence-based initiative which sees promising results every year, supporting thousands of young people to progress despite their background and individual challenges. ‘Social Mobility and its Enemies’ makes a strong case for rethinking education and employment practices in this country, and it demonstrates how much evidence is now being generated to find what works. But, while we wait for new solutions to come to light, we don’t have to stand by and see more young people leave school without basic skills and qualifications, facing an impossible climb upwards. There are many organisations in this country working to counteract these biases, often through the efforts of remarkable volunteers, proving that individual choices can also be a powerful and positive force for social mobility.

Elliot Major, L. and Machin, S., 2018. Social Mobility and its Enemies. London: Pelican books – Penguin.